Prologue

Adèle Davison writes … During the final weeks of 2016, a group of current and retired staff from the University began working with Roger Broughton to take custodianship of one of his most important projects: his Collection of Computing Artefacts. Some of this amazing collection can be seen here in his superb extensively-illustrated website: The Roger Broughton Virtual Museum of Computing Artefacts.

Roger was suffering from cancer and knew he didn’t have long to live; he was keen to ensure that his beloved museum was placed into safe hands for posterity. Sadly, Roger passed away just before Christmas.

We have put together this special newsletter as a tribute to Roger, who was a dearly loved colleague in the University until he retired in 2002.

John Law, author of this article, writes … I was an Information / User Education

Officer in the Computing Service, 1971-2009. I was asked to join the Museum

Project in December 2016. The project is chaired by Dr Will Blewitt of Computing

Science; the other members are Emeritus Professor Brian Randell and Sara Bellwood (Computing Science), Dr Clive Gerrard (now retired, formerly the head of our PC Services), Michelle Wright and Adèle Davison (NUIT); and Samantha Gray (Museum Studies).

There are several stories that could be told about computing at this University during

Roger’s time (1967–2002): the Computing Laboratory itself; NUMAC; the University Computing Service and its ground-breaking advances, emulated in the UK and in the world, our pioneering network, and its contribution to the foundation of the Internet.

Those stories may never be written, but in this tribute to Roger, I have touched upon a couple of them. I hope you find time read these notes: it might cheer you.

John Law, 22 March 2017

Two artefacts together

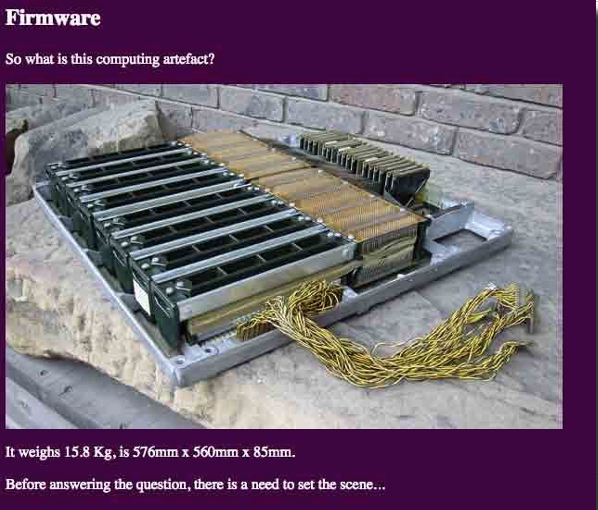

This is one of the first photos you see on Roger’s “Virtual Museum” website.

It’s an example of “firmware”, which he describes in detail on the page.

It’s from the Control Unit of the disk drives seen later (in this present article) in the “world famous” picture of our first IBM mainframe.

Here, it’s been chucked out: but Roger has rescued it. He has photographed it in the Loading Bay (the sunken area beside Claremont Road, overlooked by the entrance outside the Service Desk).

What Roger does not say (though I’m certain that he knew) is that it is sitting on a Roman altar, owned by the University’s Museum of Antiquities. They had a whole collection of these, and since there aren’t many places you can store 100+-kilo blocks of stone, they stored them in the Loading Bay for decades. Those altars (now in a safer place I believe) watched our mighty, cutting-edge mainframes arrive, and watched them depart a few years later.

Roger’s own “Museum of Antiquities” has a significance equal to those altars.

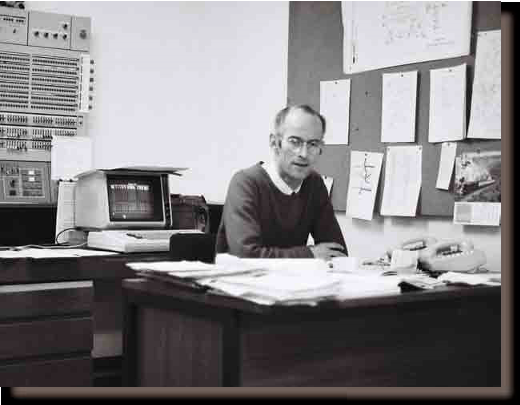

Roger E. Broughton (REB)

As our Operations Supervisor, Roger’s working life was based below Ground Floor: he spent most of his time in his particular domain, the Sub-Basement Computer Room.

Whenever I went to see him he would greet me with the softly spoken exclamation: “John!”, which somehow managed to combine a sense of surprise (“What are you doing down here?”) with a sense of “How nice to see you!” – which always made me feel good.

The Man

On “HMS Computing Laboratory”, Roger was the ship’s Chief Engineer: in his domain, which for decades was the centre of this University’s computing power, nothing went on without Roger’s overseeing it.

Up until the 90s, our “customers” very rarely saw him. However, we, his colleagues, did see him: he was at the centre of everything that moved (or rather, sat and hummed). If anyone needed to do something in the Sub-Basement, they had to go through Roger: they could expect a close grilling, but they could also expect a tremendous amount of expert help and friendly cooperation.

He made a point of trying to understand – completely – every single piece of equipment that entered his domain: a new telephone, the core drills used by contractors to bore holes in Claremont Tower’s solid concrete walls, the power supplies, up to the immensely complex installation of the mainframes, over which he had charge. This was no burden to him: a love of complex mechanisms and systems was in his DNA.

He had a lifelong love of machines, of any description, size or complexity.

Roger and brother Peter on the famous “tribike”; brother David is taking the picture.

FYI: they are at Heathrow airport!

He had a passion for finding out exactly how things worked, and if something was discarded for being outdated, or broken, he often delighted in trying to make it work again. On the other hand, whenever a new piece of technology entered our arena, Roger would be right there on it, finding out what it did, and how.

Roger also made a point of getting to know people: he believed – he simply knew – that the wheels of work turn more smoothly if people know and respect each other. Our porters and cleaners, every foreman on every job, the Fire Officers from Newcastle’s Fire Brigade, academic staff throughout the University: all knew him because he went out of his way to get to know them – not in a familiar way, but always in a friendly, professional way.

(Almost!) everyone liked him for his forthright honesty in all things. Sometimes he could rub people up the wrong way, but his reasons would usually be because he felt that they were failing in their responsibilities to the job they were being asked to do, or even simply in the responsibilities of being a good human being,

The Computing Laboratory has had many talented people, but I think that Roger was unique. He started with us, having been a mathematician at Swan Hunters (they built ships, remember?) in 1967.

Esso Hibernian at Swan Hunter’, seen from Byker, c.1969

Having joined the Laboratory, Roger’s first great task was to make sure that the NUMAC IBM 360/67 (see later) would be given its perfect home, according to very demanding specifications.

The Job

Roger’s career spanned the age of gargantuan mainframes through to microcomputers and the wonders of networking (it really was a wonder: getting your computing service at home!). In the 80s and 90s, he was at the “the bleeding edge” of assisting our academic users to work at home – first via modems, and then via ISPs and “that Internet thing” (about which there is another Newcastle story to tell).

From the 1980s onwards, the Computer Room began to be filled, not with two or three juggernauts and their attendant machines, but with scores of smaller (but more powerful) service machines, and servers, and networking equipment. Roger’s role did not change – it just got a lot more complicated.

His Operations Team moved, likewise, from feeding punched cards into incredible machines, to becoming experts in shepherding the many systems in the Computer Room … and subsequently out on campus. Under Roger’s tutelage “the Ops” also formed our first phone-in Help Desk which was a terrific service greatly appreciated by all our users from the 80s onwards. (By the way, it was not within our remit to support undergraduate students at all until the early 90s: imagine that.)

The Computing Laboratory: we go back a long way

Newcastle became a University in 1963. Before then, it was King’s College, Durham University. King’s College was where most of the Science and Engineering departments were located.

Our first Director was Professor Ewan Page (later Vice Chancellor of Reading University). It’s very instructive to read his informal CV[1] at the BCS. Here’s an edited version of the start, which shows direct links to the prehistory of computing:

In 1949 I was a student at Cambridge when Maurice Wilkes[2] offered a short course on programming an electronic computer; … I was one of about two dozen who attended. Three years later … I was doing research in

Mathematical Statistics and needed a lot of calculating (for those days) to find the properties of some cumulative sum schemes for detecting a change in observations that I had proposed. … EDSAC[3] was working, and Mauriceʼs committee agreed that I might use it … A little later in 1954 Durham University appointed me to direct their new University Computing Laboratory, soon to be equipped with a Ferranti Pegasus[4] machine. The experience of EDSAC was key to my appointment; there were very few people who had done any original work at all on a computer in 1954, …The Pegasus was the only machine in the North East ….

Professor Page was a human dynamo, very ambitious for his pioneering Laboratory.

You can see a time-line on the history of the Laboratory at Computing Science’s History pages[5]

NUMAC

The most significant single step in that timeline (i.e. in terms of computing power, all the considerable academic achievements aside) was the acquisition in 1967 of the mainframe computer, the IBM 360/67 (read all about it)[6].

Initially, only half a dozen of these machines were built by IBM in the world. They were capable of something unique: they used virtual memory to enable a new concept – time-sharing. IBM had played with the idea, were about to drop it, and then agreed to make a few examples under pressure from the computer scientists at MIT and at the University of Michigan. Our computer scientists knew their computer scientists, and hence the Computing Laboratory became the proud owners of a machine unique outside the USA.

One of the best known pictures on the Internet (if you’re googling for IBM 360/67).

This is our Computer Room. Roger says: “This is set up: the computer room was never that tidy, and that 7th switch from the left on the front of the processor is down, which means ‘DISABLE INTERVAL TIMER’ i.e. the processor was doing nothing.”

Because of the continuing close cooperation between Newcastle and Durham Universities, a joint bid was put forward to install a 360/67 in the Computer Room of the newly opened Claremont Tower. This computer cost well over £1,000,000 – over £16,000,000 in 2017 terms (money for computers was at that time awarded directly, on merit, by Government).

An organisation was created to run this computer and all its unprecedented services:

Northumbrian Universities Multiple Access Computer. NUMAC. Newcastle provided 70% of the resources, Durham the other 30%.

In 1967 the 360/67 was one of the biggest and most powerful computers in the UK.

Incidentally the main computing system weighed about 12 tons; its successor in

1975, the IBM 370/168, weighed 24 tons; but its successor in 1985, the Amdahl

5860, weighed a mere 17 tons (maybe something was happening, huh?). The 360/67 required 200m2 floor space, about half of our very large Computer Room. The Computer Room had (and still has) its own power supply. The 360 also required its own air conditioning plant, which was located in other Sub-Basement rooms. (All this kit was of course craned in via the Loading Bay, which is why it is there: the architects designed a Sub-Basement Computer Room, with all necessities.

Although they did make one little, fundamental mistake: see below.)

Roger and his colleagues worked hand-in-glove with IBM’s engineers to prepare the Computer Room, oversee the delivery, and then the commissioning. After that it was simply a case of maintaining 100% running, 365 days a year …. when the service failed, operational faults should not be the cause!

Of course there were failures – regularly: compared to modern times, this was steam age computing (sometimes almost literally if we had a flood in Claremont Tower), and so the systems (i.e. on-call experts) for dealing with them were sophisticated.

Our very first flood, c.1964?: the builders of Claremont Tower discover the subterranean Pandon Burn[7] (which has been running underneath Claremont Road since the 19th century). This one wasn’t our problem, but we’ve had several floods since, one caused by the Burn, others caused by the Tower’s central heating.

For Roger, any operational emergency was both a pain in the neck (no matter who was on call, he almost always became involved) and also a challenge, in which he usually took a certain pleasure.

The Split

The other very significant date in Computing Science’s time-line8 is 1991: it was then that the University split the Computing Laboratory into the Department of Computing Science, and the University Computing Service (UCS, later ISS, now NUIT). The split was regretted by the staff on both sides. During the 90s and 00s, the Computing Service absorbed the University’s Admin systems, and soon acquired SAP (a consultant-led decision on the part of a committee set up by the University, which quite deliberately did not have any members with computing expertise).

Roger’s Collection

Back to the Museum Of Computing Artefacts … throughout his career Roger collected machines, and bits of machines, that had become redundant. His natural inclinations aside, he knew that these items were too important just to be discarded. Being privy to places that few others knew about, he stashed them wherever space could be found.

He began to catalogue his collection after he retired, using a database which is popular with small museums. He has over 500 items catalogued; each one is marked with its number to the recommended standards; each database entry has space for up to 30 fields of information. The more that I, myself, find out about this database and the collection, the greater my admiration for Roger’s skills increases: within the limitations of his budget (i.e. zero), there are no half-measures.

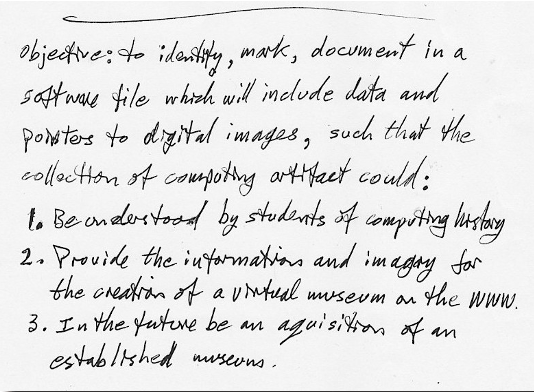

As his collection grew, he began thinking about creating a Virtual Museum: a website based upon the artefacts. Why? Well, among his papers we found the actual bit of paper … …

… … on which he had jotted down his original objectives (perhaps it was a recommendation, to do this, from the creators of the museum catalogue software that he acquired):

The Virtual Museum, and the real one

As Adèle said at the start, Roger’s Virtual Museum is now at http://moca.ncl.ac.uk/. He started his wesbite in 1994 – and it shows(!), being plain old HTML. If you trace a path through his museum you will sometimes find yourself “in a maze of twisty little passages” …. however (unlike the original Colossal Cave[8]) these passages are not all alike, but bejewelled with nuggets of fascination.

A few more glimpses of Roger’s Collection …

We discovered this lump in the corner of one of REB’s store rooms. It’s not catalogued; Clive thinks it might be part of a disk drive from the Amdahl; it weighs 158lb (there’s a warning label on it); we haven’t moved it yet.

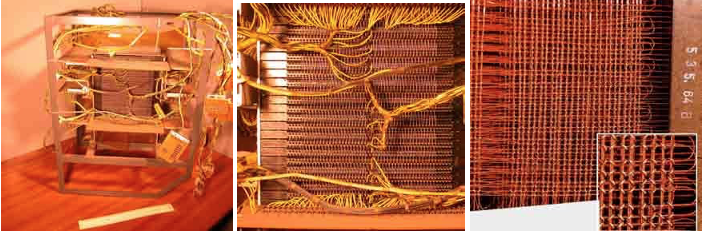

In contrast, here’s some of the core storage from the KDF9 (vintage 1963). Read about the incredible, complex, delicacy of this form of storage here10. and see more pictures of this artefact here11

Disk store: there’s a great little web page here[9] about the first photograph, which rather boggles you.

Contrast Picture 2 with “The Lump” on the previous page. This item (160GB) must be really recent but I haven’t found the web page about it yet.

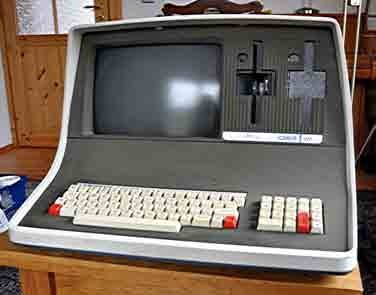

Finally, one of the first ever micros that we acquired. Yes it really was called a Superbrain. Some years ago, we found the invoice for it: it cost about £4000. But – come on! – not only did this baby have two (count ’em) floppy disk drives: it had a hard disk!

Working with Professor Brian Randell and Dr Will Blewitt of Computing Science,

Roger had already organised physical displays of historical computing equipment. One of these is a permanent exhibit in Claremont Bridge, where there are display cabinets containing some of the artefacts (go have a look: it’s outside the Tower end of “The Rack” on Floor 6).

The School of Computing Science will move in September this year to the Urban Sciences Building at Science City. 2017 is their official 60th birthday! They plan to have computing artefacts displayed prominently in the entrance hall of the building.

Most of these will be from Roger’s collection. Roger was discussing the plans with CompSci in 2016, but he didn’t live to see (or more interestingly for him: help to organise) the display.

Our tasks in the Museum Project are:

- Gather together Roger’s collection into a safe, contiguous space; Jason has kindly found us such a space.

- Verify Roger’s catalogue (over 500 objects so far) against what we have collected.

- And then in effect hand over the Roger Broughton Museum of Computing Artefacts to Computing Science, for their use and direction, in the ways in which Roger envisaged in his original objectives.

- At present, the questions of future storage and curatorship are too far in the future to be concerned about 🙂

We must now continue without our dear friend. His website is about to be taken over by Computing Science (who have exciting plans for a VR rendition). They will make it somewhat fancier, and it will get a rigorous editing, but the substance of it will remain the same: Roger was all about content and accuracy, not style.

[1] http://www.bcs.org/content/ConWebDoc/54755

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Wilkes

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_delay_storage_automatic_calculator

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferranti_Pegasus

[5] http:///www.ncl.ac.uk/computing/about/history/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_System/360_Model_67

[7] http://blog.twmuseums.org.uk/the-real-barras-bridge-and-newcastles-beautiful-lost-dean/ 8 http:///www.ncl.ac.uk/computing/about/history/

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colossal_Cave_Adventure 10

http://moca.ncl.ac.uk/corestore/h3wcsw.htm 11

http://moca.ncl.ac.uk/corestore/KDF9cs.htm

[9] http://moca.ncl.ac.uk/corestore/512MB2004.htm